Jean Overton Fuller

1915 – 2009

W R I T E R -

A M E E T I N G O F M I N D S:

Letters to Dr Megs Little

.. Miss Overton Fuller’s task in finding out the truth behind the wartime mysteries

has been life-

Miss Fuller was also un-

I had to refuse the offer for film rights in the Dericourt. Matter has been dragging on since May. I first asked that the script should be submitted to my approval; was told this was impossible. Now I understand that to make a film costs hundreds of thousands of pounds, and that the financiers would not want to invest the money only to have the author disapprove and veto project when money had been spent.

Jean in 1980

Megs in Frankfurt, 2003

Megs and Georgette in 1965

This section is a glimpse into a correspondence of thirty-

A first meeting was in 1952, when Margaret and her German mother, Georgette Hutchinson

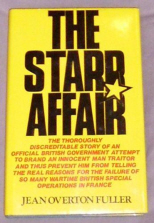

(née Schwartze), attended Miss Fuller’s lecture on her book, The Starr Affair. It

was fresh thinking in the Post-

You were at a place called the Carver Institute in Cheshire, giving a pre-

That somebody in authority should actually have gone into post-

Until about 1944 my mother concentrated on trying to believe that all the atrocity stories were propaganda (she concentrated all the harder because she knew that her own mother had been imprisoned for listening to English radio in Frankfurt), and after 1944, when the Belsen pictures were in all the papers and there was no longer any getting away from the facts, she had a kind of identity crisis and wanted to reject all the German parts of herself and her children; which, needless to say, could not be done. So we were grateful to you.

.. We knew some Germans had had consciences – my mother had had relatives, including her own parents, imprisoned by the Nazis. But this was 1952. Everyone remembered those newsreels from Buchenwald. A lot of people still remembered the World War One trenches, too. Germans were villains and that was that, and history would never forgive them.

Certainly our own little town, right on the edge of the Manchester blitz, had had

no intention of forgiving anybody. Your lecture there must have been a bombshell

– even though I’m sure most people there were chiefly impressed by revelations of

intrigue and incompetence in Baker Street, rather than by the Avenue Foch soul-

Consequently, Margaret followed Jean’s writing career. The Swinburne biography, Margaret’s favourite poet, was of particular interest. In 1976, this Swinburne connection prompted Margaret’s first letter to the author. She sent details of a property for sale at Cleveden Crescent, Kelvinside, Glasgow, a place where Swinburne stayed on his visits to the city. The letter was received with great pleasure – it was a meeting of minds – and their correspondence continued. A strong friendship grew, even though the women lived at opposite ends of the country and only had one further meeting.

A month after the first letter, Margaret visited Jean in her Wymington home and they made an impromptu drive to Hatfield to support research into the life of Sir Francis Bacon. With her medical background, Margaret assisted with the detailed theories concerning genetic eye colour to discover Bacon’s true parentage.

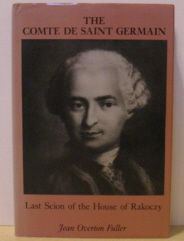

Later, Margaret and her family made German translations for the Comte De Saint Germain biography. Margaret’s husband John, a physicist, was also a reference on matters of science.

The letters reveal the struggles to get the often controversial manuscripts accepted for publication and even then, adapted many times into a particular format. A challenging task on a manual and later, an electric typewriter. Margaret writes:

Thank you so much for telling me about all your former books and their vicissitudes.

I knew you had had a lot of trouble with the authorities over the war books; I did

not realise there had also been problems in getting them published. It really is

ironical, for in the end they were best-

As you say, this realisation is so universal now that it is hard to remember how unsophisticated the public was twenty years ago. You must have contributed much to the brotherhood of man in Europe, because what emerges so clearly from the books is that the true frontiers are not between nations or systems of government, but between human beings with integrity and those with none.

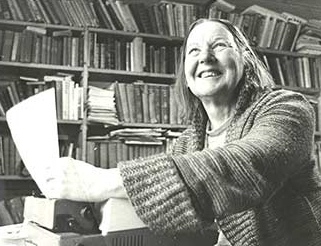

Theosophist C. W. Leadbeater’s chakra points

Jean replies:

I am much interested by your dream of my house. Mirrors, of course, are strange, magical things, reflecting and reduplicating images. I have, in my time, been on the “inside” of many mysteries – mysteries leading into and “reflecting” other mysteries – so my house containing a hall of mirrors could have to do with that. Yes, but how to get my mysteries out before the public? That is still my problem. I still have heard no further from Gollancz, keep touching wood and waiting for every post in terrible anxiety and hope.

My furred and feathered companions are great restorers. When during my morning’s meditations I find Bambina [a cat] sitting between my crossed knees or feel the touch of her whiskers or fur, it makes my day. And Delia, who has now grown into a beautiful hen, still perches on my shoulder. She has learnt to fly in and out of the window of the bathroom, in which she still sleeps, and lays an egg for me regularly, every day, copper like her plumage. She is the glossiest hen I have known, looks as though she had been waxed, though against my cheek her feathers are as smooth as silk.

In January 1994, Megs comments on a poem Jean sent about the burglary in her Wymington home and the loss of precious family items.

Megs was once asked for a physiological insight into the body’s seven chakra points and the phenomena of the kundalini rising. They discussed the possibility of a correlation between the glands, nerve or “reward centres”. Miss Fuller further comments: One point I am making is that there is one place where Kundalini is most powerfully felt, which is never mentioned in the books and has no chakra or Sanskrit letter allocated to it, and that is the base of the neck, or rather, in the first of the big, knobbly bones that one feels, if one places one’s hand behind one’s neck and feels one’s way down over the bones. That is where one feels it when one begins to think meditatively. A mystery.

One unusual exchange in 1986 is where Megs describes a dream:

Your house in Wymington, in my dream, was just as I remember it from the outside – but inside, like the hall of mirrors at Versailles, with magnificent blue and red oriental carpets to boot. Any suggestions? I wondered, afterwards, whether it was a metaphor for the wealth of material on France, Dericourt, etc., you have not yet given the public. (I was a kind of spectator, looking down from a gallery.)

With this, Miss Fuller had such a strong core belief in herself and that behind everything there was a guiding hand for her highest good. After another failed driving test she writes:

I am one with the Absolute and Infinite All, the source and plenitude of all capacities, and therefore, to do everything and anything, however little I may be gifted for it, must be – is – within my capacity, and I shall go on until I succeed, or until the end of this incarnation, to give myself a chance in the next.

To conclude, a poem written by Megs for her friend in November 2001. They had been discussing memory in childhood, while Jean was writing her autobiography Driven To It. She asserted that she had clear recollections from her earliest days. As a scientist, Megs could only say this was unusual, but in her thinking she tried to avoid the words “never” and “always”. This grace was the essence of a respectful, long lived friendship.

Dear Jean, these Solstice poems

Are absolutely beautiful. That child

Who said “The flowers are flying” lives in you

Uncluttered and untwisted, still is you

As bright and burning as that summer’s day

In far-

Most memories of childhood slide and flit,

Distort, support a later, cloudier self

And justify some failure, then or now.

Not yours.

You were, you are, yourself still young

Still drinking in the rhododendron’s dew

In face-

And waited by locked doorways for some truth

To surge in sweetness from its hidden place.

Poem first! – longer than usual, and very beautiful, and very immediate. I held my breath reading it, and felt so sorry for your losing all the mementoes (though not the memories) of your childhood, and angry about it too, and so relieved when Alexander [her cat] turned up – though of course I knew he would.

Your lines about what psychoanalysts call object relations are very apt

“The things that had been round about me

Were now within me

The external

Internalised – “

This kind empathy must have been a great consolation to Jean, a woman living on her own without family. Megs’ encouragement was constant, whether it concerned her books or the matter of twelve attempts to pass her driving test. (That done, Jean would drive down to London to visit Tim d’Arch Smith, her dear friend and business partner.)

Sketches of some stolen items

So, I drew up what seemed to me minimum conditions, to be agreed before starting. They were, 1 that Dericourt should not be turned into an agent of Dansey, M16, the Soviet Union or merely a German agent or mercenary crook, 2 that a fictitious heroine should not be substituted for his wife, 3 that neither Ernst Vogt nor Goetz should be turned into “baddies” or represented in a manner they would not wish, and 4 that a fictitious torture scene should not be introduced. On 4 Dec., I had a letter from Vitali saying my conditions were “impossible” – just repeating his offer, which was by now 2 and a half times the original offer and more than seven times the sum I accepted for film rights of Noor. It was the largest sum of money I had ever said “No”, to, but there was nothing else to do, so I instructed my film agent that day to refuse on my behalf and ask for my typescript back – because it contains matter which, until the book is out, is confidential.

Some letters are a fascinating dialogue between the viewpoints of science and faith

-

I love the word-

After reading Conversations with a Captor – Megs’ personal favourite – she again identifies (in a letter dated September 1996) the unique contribution of Fuller’s war books:

Although of course much of the material is familiar from your other books – The Starr Affair, which I read first more than forty years ago, and Madeleine and Double Webs and Dericourt and Conversations with a Captor which I’ve read since – it is helpful as well as impressive and scholarly to have it all summarised here. And I found your last chapter, “Reflections”, greatly moving. One doesn’t usually find so much dispassionate attention to detail combined with a personal affirmation of that kind. So often books are either one or the other – detail with no soul, or passion without enough supporting facts. When I try to put my finger on the unique thing about your books (apart, that is, from all the extraordinary places you went to and extraordinary people you met and extraordinary things you did back there in the forties and fifties) – I keep coming back to the balance between fact and feeling, for there is so little of it around and it is so precious.

Contentious matters did not rest once the books had been published. There were attempts to plagiarise Fuller’s biography of Noor Inayat Khan or to fictionalise and distort the facts. Jean was fierce in protecting the legacy of her friend Noor, as seen in the article from the Northamptonshire Chronicle & Echo of April 18, 1980:

Writer Miss Jean Overton Fuller is angry about the television serial on the life

of her close friend, British secret agent Noor-